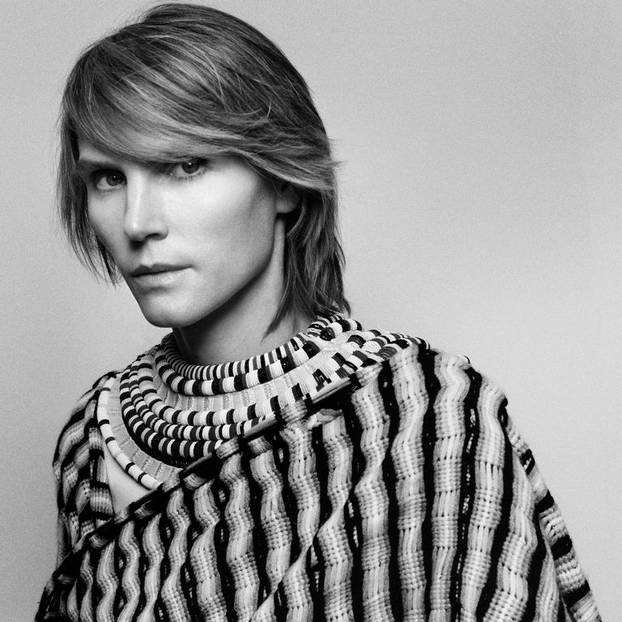

Gabriela Hearst Is Fashion's Earth Defender

Growing up on a ranch in Uruguay, Gabriela Hearst learned a valuable lesson from riding horses. When the animal suddenly bolts, you can either panic or go with the flow, she explains: “My upbringing [exposed me to] dangerous situations where I had to act and react.” Her instinct now is fight, not flight. “I don’t get paralyzed with fear. I take action.”

That damn-the-torpedoes approach has helped Hearst stare down the existential challenge that is climate change. Since founding her eponymous brand in 2015, she’s worked tirelessly to reshape the industry in a more sustainable image, setting the benchmarks for others to follow. For her fall 2017 show, she used dead stock, or unsold surplus fabric. At the time, “that was kind of a bad word to use with ‘luxury’ next to it,” she recalls. “And now it’s becoming common practice.” Two years later, she held the first-ever fashion show to be certified carbon-neutral; for spring 2021, she offset her show’s carbon footprint with a donation to EcoAct’s Madre de Dios Amazon Forest Conservation Project. “I never realized we were going to be the first show that ever mentioned their carbon footprint,” she says. “And now, looking back, I realize that what we were trying to do was bring accountability and data collecting to our industry.” Her current goal: transitioning to 100 percent repurposed materials by the end of the year or early 2022 (“Right now we’re at around 50 percent,” she says). And having recently been named the creative director of Chloé, Hearst will now have a bigger platform for her activism.”

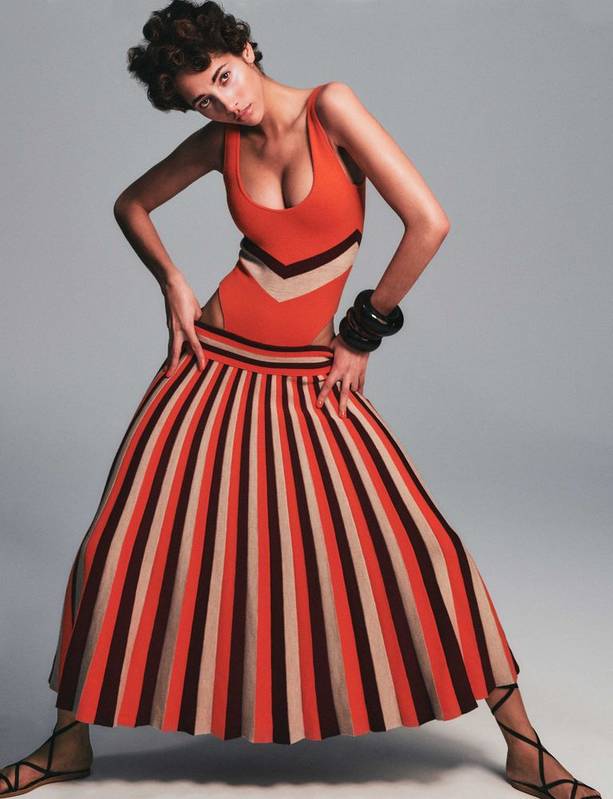

As with climate change, the pandemic has presented a case of clear and present danger for us all. Over the past year, Hearst says, “I shifted to trusting my gut more than my brain.” Her subconscious took the wheel, and she dreamed about her late grandmother, imagining herself knotting cloth on her back to create a dress. “A dream of reassurance,” she called it. Another talisman that brought solace was a shell bracelet from Rapa Nui (Easter Island) that her mother had given her right before the pandemic hit. Those two threads found themselves intertwining in the spring 2021 collection Hearst showed in Paris in October, appearing in the knotted back of a dress and in the shells clinging to the edges of gowns’ cutouts. The collection, titled “Dreams of Mothers and Grandmothers,” was steeped in the comforting idea that generations of women had tackled seemingly impossible challenges before.

- The designer has always fought for conservation, and her spring collection is rooted in the ultimate sustainable tradition: craft.

Elle Magazine

It also incorporated craft, which is, aptly, a traditionally female practice often passed down from mothers to daughters. Around 80 percent of the collection was made by hand. “Braiding shells on a dress is something a machine cannot do,” Hearst says. The magic of the process lay in “human imperfection, and then the imperfection transforming to [something] marvelous. We are, at this company, believers in trying to save as many crafts as we can.” Such tactile arts also offered a way to feel more connected to the physical in a digital sphere. “I think that’s one of our big challenges,” Hearst says. “We’re so physical, so human. It’s challenging to express that in the digital world.” She asked herself a question we’re all grappling with these days: “How can you emote and provoke [while] being mostly digital?”

It also incorporated craft, which is, aptly, a traditionally female practice often passed down from mothers to daughters. Around 80 percent of the collection was made by hand. “Braiding shells on a dress is something a machine cannot do,” Hearst says. The magic of the process lay in “human imperfection, and then the imperfection transforming to [something] marvelous. We are, at this company, believers in trying to save as many crafts as we can.” Such tactile arts also offered a way to feel more connected to the physical in a digital sphere. “I think that’s one of our big challenges,” Hearst says. “We’re so physical, so human. It’s challenging to express that in the digital world.” She asked herself a question we’re all grappling with these days: “How can you emote and provoke [while] being mostly digital?”

Hearst’s work focuses not just on the traditional environmental definition of sustainability but on “the social component of who is making the clothes. And as simple as it may sound,” she says, “happy people make happy clothes. I’m a big believer in the consciousness of a product.” Some of the spring collection was made by Manos del Uruguay, a nonprofit she’s been working with for years that employs hundreds of women—which, she points out, is a significant bloc in her home country of nearly 3.5 million people. At Manos, which has been around for over 50 years, “you see mothers and daughters working [together],” she says. “The older I get, the more I enjoy the company of women. I feel that we get very witchy with age.” Each of Manos’s pieces is emblazoned with the name of the woman who made it, connecting the wearer to the process. But, she notes, “I work with them, not [just] because of their good intentions, [but] because they make a beautiful product and they understand my aesthetic. I don’t think anyone’s going to buy us for our good intentions. They’re going to buy us because the product speaks to them as desirable.””

Hearst will surely bring her commitment to eco-friendly design to her buzzy new post at Chloé, where she recently presented her first collection for fall 2021. The pandemic “has shown us that we can change our habits really quickly,” she says. “I keep myself hopeful, because I do really believe that we’re going to be able to pull ourselves from the brink.”